Table of Contents Show

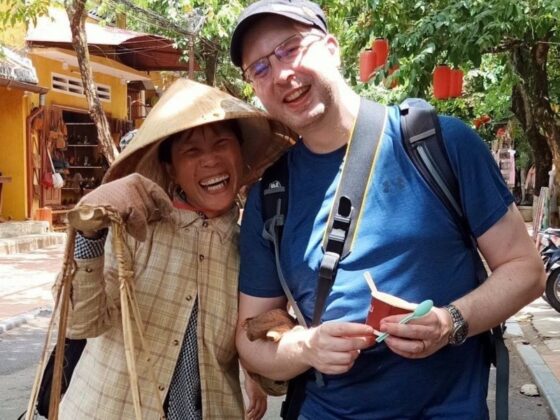

For the European traveler, Vietnam offers a fascinating cultural mirror, reflecting a shared, albeit complex, history. The French colonial period—often termed Indochine—did not simply impose foreign forms; it initiated a profound cultural dialogue. The true genius of Vietnamese culture was its ability to absorb these influences, from architecture to gastronomy, and transform them into something uniquely functional, beautiful, and utterly Vietnamese. This legacy isn’t hidden in museums; it’s tasted on the street and seen in the elegant facades of the cities, especially within the French colonial architecture Vietnam.

Read more interesting posts here:

- Vietnamese Fine Dining: Beyond the Pho Stall to Gastronomic Heritage

- Stilt Houses Vietnam: The Living Legacy of Hmong Architecture and Community Life

- History of Vietnamese Coffee: From Colonial Import to National Fuel

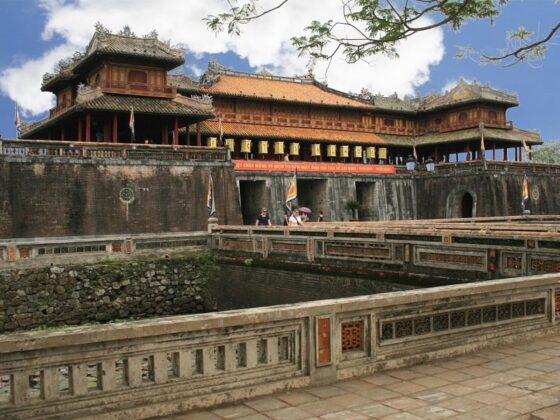

Architectural transformation: From grandeur to adapted French colonial architecture Vietnam

The French architectural footprint extends far beyond the grand administrative buildings like the Hanoi Opera House or the Saigon Post Office. The most resonant legacy is how colonial design principles were adapted for daily Vietnamese life in the country’s French colonial architecture Vietnam.

- The most fascinating element is the Indochine Style. This hybrid aesthetic, prevalent in villas and shophouses in cities like Hanoi and Đà Lạt, is a perfect blend of European Art Deco and traditional Vietnamese elements. You see this in the elegant, arched windows, the use of cooling terracotta tiles, and subtle geometric carvings—a style that respects both the colonial need for formality and the tropical demand for ventilation. This blend is a direct, silent cultural conversation rendered in plaster and stone.

- Equally compelling is the Residential Adaptation seen in the urban cores. The French introduced elements like balconies and decorative facades to the traditional Vietnamese “Tube House” (long, narrow homes designed to maximize street frontage). This adaptation resulted in charming, functional urban homes that blended European-style light and airflow with Vietnamese density and communal living, a subtle but widespread element of French colonial architecture Vietnam. Seeking out these residential streets offers a niche architectural tour that tells a deeper story than any landmark.

The culinary synthesis: Mastery in the kitchen

The French legacy is most deliciously evident in Vietnamese cuisine, where foreign ingredients and techniques were seamlessly integrated and perfected, complementing the changes seen in French colonial architecture Vietnam.

- The Bánh Mì Revolution is the ultimate synthesis. The French introduced the baguette; the Vietnamese claimed it. The result is the Bánh Mì—a crispy, light baguette filled not with butter and cheese, but with traditional Vietnamese components: pâté, chả lụa (pork sausage), cured meats, fresh cilantro, chili, and pickled vegetables. This fusion elevated the simple sandwich into an inexpensive street food staple, costing between $0.75 and $2.00 USD, making it an incredibly accessible piece of cultural history.

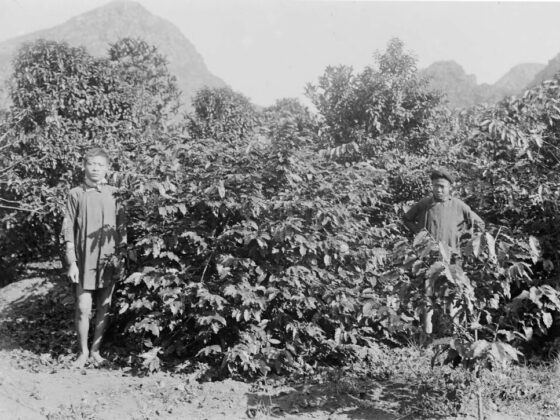

- Furthermore, the Highland Agriculture system was reshaped by the French. Realizing the unique, cool climate of Đà Lạt was perfect for European crops, they introduced high-quality vegetables like artichokes, potatoes, asparagus, and strawberries. This profound legacy of agricultural transfer transformed the Central Highlands into the “vegetable garden” of Vietnam, fundamentally shaping modern Vietnamese cooking.

- Finally, while bia hơi (fresh draft beer) dominates the casual drinking scene, the enduring French legacy means wine and soft cheese (relative to other Southeast Asian countries) are more readily available. This sophisticated touch occasionally incorporates itself into the modern fine dining scene, providing a continuous thread back to the colonial table, albeit adapted for local palates and tropical weather.

Conclusion

Vietnam didn’t just inherit the French legacy; it absorbed it, adapting the forms and flavors to suit its climate and its culture. The legacy of French colonial architecture Vietnam—particularly the functional elegance of the Indochine Style—is a brilliant testament to the nation’s ability to create a vibrant, enduring synthesis that is truly unique. This cultural dialogue, visible in grand public buildings and humble residential homes, continues to shape the aesthetic and culinary identity of modern Vietnam.

Join our vibrant community on Facebook to share your trekking stories and tips, and don’t forget to like the ExoTrails fanpage for the latest updates and exclusive offers!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Where can I see the best examples of French colonial architecture Vietnam?

A: Excellent examples can be found in Hanoi (e.g., Opera House, Old Quarter) and Ho Chi Minh City (e.g., Post Office, Notre Dame Cathedral).

Q: What is the defining characteristic of the Indochine Style?

A: It is a hybrid aesthetic that blends European elements, like Art Deco facades, with traditional Vietnamese features such as cooling terracotta tiles and emphasis on ventilation.

Q: How did the French influence residential French colonial architecture Vietnam?

A: They introduced features like balconies, decorative facades, and better airflow designs, which were integrated into the traditional “Tube House” structure.

Q: What famous Vietnamese food is a direct result of the French colonial legacy?

A: The Bánh Mì sandwich, which adapted the French baguette with traditional Vietnamese fillings, is the most famous culinary synthesis.